Chapter Four

VENICE IN FESTIVAL

THE treaty signed in 1573 between Venice and Constantinople, though it marked no real rise in her fortunes, gave her a respite from the petty and fruitless warfare with the Turk, in which she had so long been engaged. That conflict had drained the resources of the Republic without affording compensating gains. The loss and horrors of Famagosta might seem to have been revenged by the battle of Lepanto, where the triumph of Venice and her allies was complete; but owing to the dilatoriness and inaction of Don John of Austria, brother of Philip of Spain, the opportunity of annihilating the Turkish forces was allowed to escape, and victory was reduced to little more than the name. So flagrant had been the character of Don John’s disloyalty that the Venetians no longer could mistake his intentions. Spain was an ally of Venice; but Tommaso Morosini was but voicing the general conviction when he exclaimed, “We must face the fact that there will be no profitable progress, seeing that the victory already gained by the forces of the League against the Turk was great in the number of ships captured, rare in the number of slaves set free, famous by reason of the power it broke, formidable for the numbers killed by the sword, glorious for the pride it laid low, terrible in the fame acquired by it. And, none the less, no single foot of ground was gained. Oh, incomparable ignominy and shame of the allies, that whatever honour they obtained in consequence of the victory, they lost by not following it up!” Though nominally in league with her against the Turk, Spain, owing to her jealousy of Venice, was unwilling that the war should be ended. The League of Cambray, formed in 1508 by the European powers unfriendly to Venice, should have made it clear to the Republic that she had over-reached her own interests by interference in the politics of Europe. Moreover, a severe blow had been dealt to the commerce of Venice by the discovery of the Cape route to the East. Yet, though her decline had begun, she still formed a subject for envy, and there is justice in Morosini’s conclusion as to the causes of the growing enmity of Spain. “Ruling,” he says of the Spaniards, “a good part of Europe, having passed into Africa, having discovered new territory, dominating most of Italy, and seeing the Republic, the single part, the only corner of Italy, to be free and without the least burden of slavery, they envy it, envying it they hate it, and hating it they lay snares for it.”

Though the terms of the peace with Constantinople were humiliating in the extreme (Venice relinquished the whole of Cyprus, a fortress in Albania, and agreed within three years to pay an indemnity of one hundred thousand ducats) it set her hands free for awhile and gave her a breathing space in which to return to her pageants. And for the next few years she laid herself out more completely than ever before to impress the world by her splendour. It is not easy to determine the beginnings of decadent luxury in Venetian history. Venice had always been a pleasure-house, a place of entertainment for kings and emperors, a temple of solemn festival. Perhaps the broad difference between the splendours of the early and late Renaissance is that one achieved that perfection of taste which robes luxury in apparent simplicity, while the other was more obvious and expansive—the difference between the Madonnas of Bellini and of Titian, between the interiors of Carpaccio and Paul Veronese. There is a real and discernible difference in aspect between Venice of the fifteenth and Venice of the sixteenth century, but it is not the difference between asceticism and luxury. Venice was never ascetic, no prophet ever drew her citizens round a sacrificial bonfire on the Piazza. On the other hand it is said that a Venetian merchant was burnt in effigy on Savonarola’s pile because he had attempted to purchase some of the doomed Florentine treasures. In the course of the fifteenth century isolated voices were indeed raised in protest against the luxury of Venice, and the authorities themselves, as the State coffers grew empty, tried by oratorical appeal and detailed legislation to curb the extravagance of private citizens. But their protests were, in the main, quite ineffectual. Venice could not resist the influences that wove for her each day a magical dress; she could not refuse the treasures of the East: it was her function to be beautiful, to accept and love every wonder, to turn her face against nothing that could glorify. She had always appeared as a miracle to men, she had always lavished her treasures on her guests; the vital difference between the period of her decline and that of her greatness lies in the gradual relaxation of the ties binding her to the sources of her wealth. With the ebbing of her trade her citizens begin to barter their landed estates and their treasures. Morosini’s acute and interesting prophecy as to the private banks into which Venetian money began to be diverted provides us with a background to some of the almost fabulous expenditure of the Cinquecento—“The banker,” he says, “with a chance of obliging many friends in their need, and acquiring others by such a service, and with power to do so without spending money, simply by making a brief entry, is easily persuaded to satisfy many. When the opportunity arises of buying some valuable piece of furniture or decoration, clothes, jewels and similar things of great price, he is easily persuaded to please himself, simply ordering a line or two to be written in his books—reassuring, or rather, deceiving himself with the thought that one year being passed in this way, he can carry time forward, and pass many years in the same manner, scheming that such an affair or such an investment as he has in hand, when it has come to perfection, ought to prove most useful, and that through its means he may be able to remedy other disorders; which hope proving fallacious shows with how little security walks one who places his thoughts and hopes in the uncertain and inconstant issues of events.”

The fabric of sixteenth-century Venice was too largely founded on the “uncertain and inconstant issues of events,” but none the less it was as radiant a fabric as any that man has yet fashioned. Something at least of its nature may be learned from the details of the entertainment of Henry III in Venice, and his lodging and reception in the then fashionable suburb of Murano. Henry came to Venice in the early summer of 1574, on his way from Poland to take possession of the throne of France vacated by the death of his brother Charles IX. He came at a moment when Venice was rich in artists to do him honour—Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Palladio and Claudio Merulo: he was crowned with the laurels of war; while the Republic was able to clothe herself in the glory of Lepanto and the respite of her newly concluded peace with the Turk and, superficially at least, appeared peculiarly fitted to welcome him. The young King was gracious, and greedy to drink his fill of life, and Venice was unique in her celebration. The visit was one of the most spontaneous, the most joyful to host and guest, of any that are recorded in her annals. All the territory of Venice was prepared to honour him, and his journey was a triumphal progress. There is something joyous still about the little inland cities of his route, echoes of festival still linger in their streets, romance still dwells in their hearts. At Treviso, where the young King was welcomed with peculiar pomp, the Lion of St. Mark, portrayed by three successive ages, rules still, his majesty sustained by the sturdiness of life that moves in the city. The winding cobbled streets are full of bustle and interchange, the arcades are full of people, vital and busily employed. Treviso is not a museum. Its ancient palace of the Cavallieri is still in use, though its loggia with traces of rich fresco is filled with lumber. But we are not critical of small details at Treviso; we thank it for its winding streets and for its leaping azure river; we thank it for its countless ancient roofs and painted rafters; for its houses high and low, harmonious though endless in variation, for the remnants of fresco, shadows no doubt of what once they were, but companionable shadows—horses with still distinguishable motions, graceful maidens both of land and sea. These glories are fading but they have substance still, and on a day of mid-autumn we are well able to imagine a kingly procession on the road from Treviso to Mestre. It seems a pageant, a progress of pomp and colour, as we pass between the vineyards and maize fields and the great gardens and pastures of the villas, down the avenue of plane trees set like gold banners on silvery flagstaffs with carpets of fallen leaves at their feet. Behind them are ranked dark cypresses, pale groups of willow, or companies of poplar. And these are often garlanded to their very summits by crimson creepers, and interspersed with statues, not perhaps great in workmanship, but tempered and harmonised into beauty by the seasons. Here and there is a lawn flanked by dark shrubbery, or a terrace ablaze with dahlias and salvia. And, among them, Baron Franchetti of the Cà d’Oro has a home even more worthy of the golden title than is his palace on the shores of the Grand Canal—a place where the sun reveals miraculous hangings in the shrubberies, sumptuously furnished with scarlet and crimson and gold.

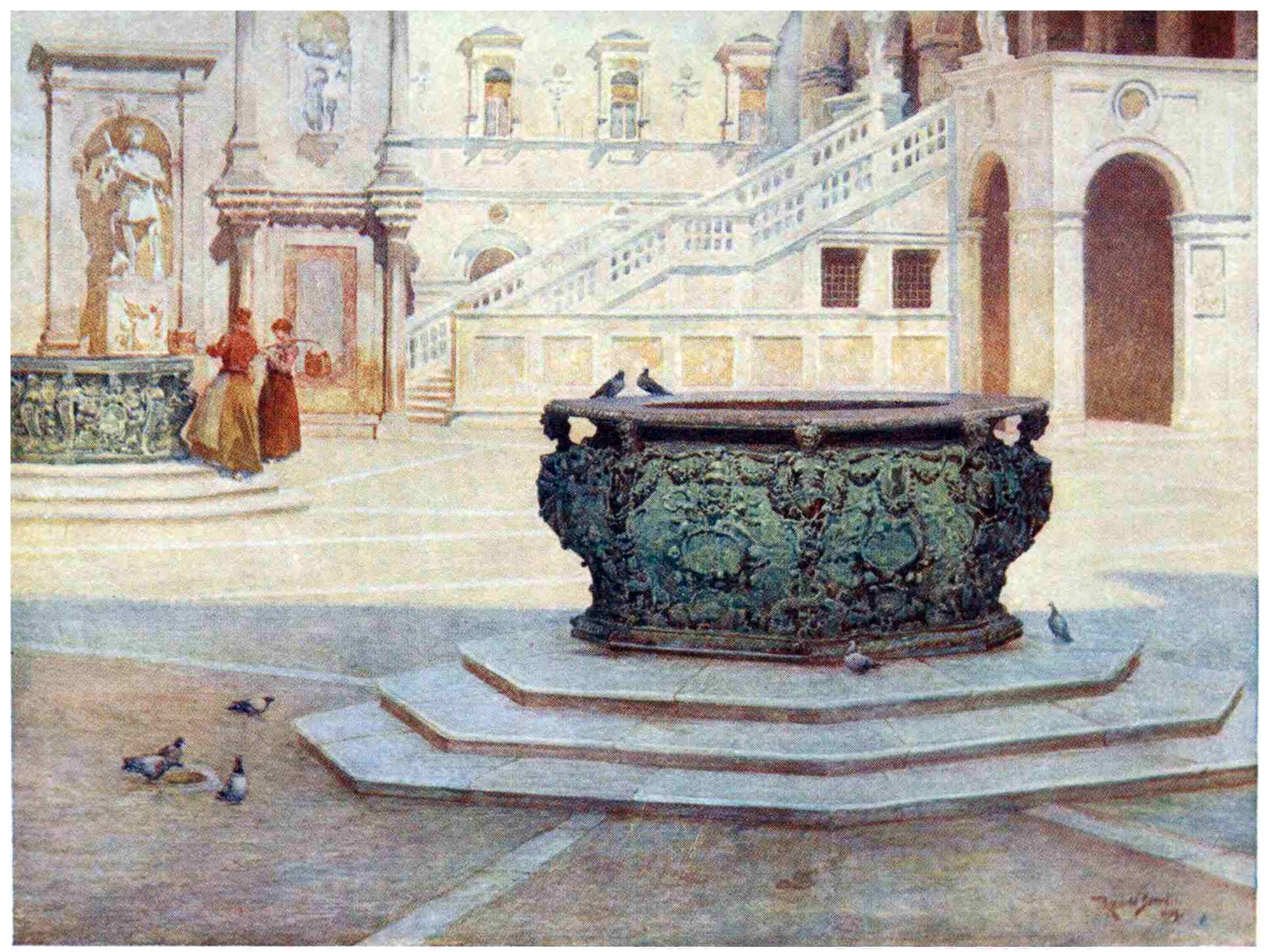

VIEW FROM CÀ D’ORO.

Some such festival of colour, in banners and trappings, would be Henry’s preparation for the pageant of the lagoons. For he was met at Marghera, half way between Mestre and Venice, by a troop of senators and noblemen and ambassadors, and escorted to the palace of Bartolomeo Capello at Murano. Of the young King’s lodging at Murano we have spoken elsewhere—of the hall hung with gold brocade, with golden baldaquin, green velvet and silk, its entrance guarded by sixty halberdiers armed for the occasion with gilt spears borrowed from the chambers of the Council of Ten. Forty noble youths, in glorious attire, had been told off to wait on the King. But, “although a most sumptuous supper was prepared, none the less His Majesty, when the senators were gone, showed himself a short while at the windows dressed in cloth of gold and silk; after which he went to supper, and the princes arrived, so that it was most glorious with abundant supply of exquisite viands and most delicate foods.” The hearts of the Venetians were won by the King’s beauty and youth, by his delicate person and grave aspect, by his majestic bearing and his eagerness to please and be pleased. He was in mourning for his brother, but his mourning did not shadow Venice by its gloom. “His Majesty appeared in public dressed all in purple (which is his mourning) with a Flemish cloak, a cap on his head in the Italian mode, with long veil and mantle reaching to his feet, slashed jerkin, stockings and leather collar, and a large shirt-frill most becomingly worn, with perfumed gloves in his hand, and wearing on his feet shoes with heels à la mode française.”

It would be tedious to relate the details of the splendid entertainments that each day were provided for his delectation; of salutes that made the earth and water tremble, of fireworks glowing all night beneath the windows of the Cà Foscari, of the blaze of light from the candles set in every window and cornice and angle of the buildings along the Grand Canal, of the gilded lilies and pyramids and wheels reflected in the water, “so that the canal seemed like another starry sky.” It was a veritable gala for Henry; he paid a private visit to the Doge to the great satisfaction of that prince and his senate, he went about incognito in a gondola alone with the Duke of Ferrara, “so that when they thought he was in his room, he was in some other part of the city, returning home at an exceedingly late hour accompanied by many torches, and immensely enjoying the liberty of this town; and on account of his charm and courtesy, the whole place gave vent to the lasting joy and satisfaction it felt in continually seeing him.” He spent three hours in the Arsenal, engrossed in viewing the vast preparation for war and the spoils won from the Turk “in the sea battle on the day of the great victory”; and then in the chamber of the Council of Ten, within the Arsenal, he was provided with a Sugar Feast, with sugar dishes, knives and forks, so admirably counterfeit that His Majesty only realised their nature when his sugar napkin crumbled and a piece of it fell to the ground. Is there not something contributive to our picture of Venice the entertainer, in this feast of sugar given by the terrible Council of Ten within the walls of the Arsenal itself? There is naturally much vague repetition in the chronicles of the time, but here and there are vital touches which bring the young King to life before our eyes. At the banquet given in his honour in the Sala del Gran Consiglio, having eaten sufficiently himself, he brought the meal to an end before half of the courses had appeared, by adroitly causing the Dukes of Savoy and Ferrara to rise in their places at his side, and calling for water for his hands during the disturbance caused by the lords and ambassadors as they followed the example of the dukes. He told Giovanni Michele that of all the entertainments he had witnessed in Venice none had pleased him more than the “Guerra dei Ponti,” and that if he had known of it earlier he would have prayed to have had the spectacle repeated several times, for he “could have asked nothing better than this.” The Guerra dei Ponti were wrestling matches that took place on certain bridges over the canals, and pages of description might not have told us as much of the nature of the man who lived behind the scented gloves and purple mantle, as this single expression of preference.

Two episodes in the visit of Henry that seem worthy of fuller record stand out from the rest: his reception at the Lido and the Ball in the Ducal Palace; and they represent the achievements in his honour of two departments of Venetian activity, the City Guilds and the Court. While he was still in his lodging at Murano barges of immense splendour, vying with each other in symbolism and ingenuity of design, and each representing one of the trades of Venice, had arrived to accompany him to the Lido. If we imagine the Lord Mayor’s Procession, with splendour a thousandfold enhanced and with drapery and design of artistic excellence, removed from the streets to the glittering surface of the lagoon, we may have some idea of the spectacle. Among the most splendid of the barges was that of the Druggists, with an ensign of the Saviour riding on the world. “The outer coverings themselves were of cloth of gold, and below them and below the oars were painted canvases. The poop was hung within with most beautiful carpets, and on the four sides four pyramids were erected of sky blue with fireworks inside them, at the feet of which were four stucco figures representing four nymphs, and there were set two arquebuses and a musket and two flags white and red and a flag of battle. And on the outside were divers sorts of arms, spears and shields and six arquebuses. On the prow was a pyramid with fireworks, on the top of which was an angel—for this and the Golden Head were the badges of the two honoured druggists who had decked the said vessel—and in the midst of it was a design of a pelican with a motto round it in letters of gold, Respice Domino, representing the pelican as wounding its breast to draw blood from it to nourish its offspring, just as they, the druggists, faithful and devoted to their prince and master, gave and offered to him, not only their faculties but their blood itself, which is their own life in his service; and at the foot of the pyramid was a little boy beating a drum.” The Looking-Glass Makers also had prepared a magnificent barge glittering with symbols of their profession. But perhaps the device of the Glass-Workers of Murano out-rivalled all others in ingenuity and pomp. “On two great barges, chained together and covered with painted canvases, they had erected a furnace in the form of a sea-monster; and following the train of vessels, flames were seen issuing from its mouths, and, the masters having given their consent, the Glass-Workers made most beautiful vases of crystal, which were cause of great pleasure to the King.”

The Convent of Sant’ Elena was the vantage point chosen for looking on Venice, and at the moment the army of barges and brigantines reached it, they spread out in front of His Majesty, and a salute broke from them all; “to which the galleys in the train of the King replied in such ordered unity that His Majesty rose to his feet with great curiosity to see them, praising exceedingly so wonderful a sight, admiring to his right the fair and famous city marvellously built upon the salt waters, and on the left a forest of so many ships and vessels with so great noise of artillery and arquebuses, and of trumpets and drums, that he remained astounded; while he openly showed himself not less merry than content, seeing so rare a thing as was never before seen of him.” Henry’s arrival at the Lido is portrayed in the Sala delle Quattro Porte in the Ducal Palace. He is seen advancing with sprightly step, between two dignitaries of the Church, up a temporary wooden bridge towards the Triumphal Arch and Temple of Palladio. This arch was decorated with paintings by Paolo and Tintoretto, and in connexion with it Ridolfi tells a delightful story of the painting of Henry’s portrait. “Tintoretto,” says Ridolfi, “was longing to paint the King’s portrait, and in consequence begged Paolo to finish the arch by himself; and, taking off his toga, Tintoretto dressed himself as one of the Doge’s equerries, and took his place among them in the Bucintoro as it moved to meet the King, thus furtively procuring a chalk sketch of the proposed portrait, which he was afterwards to enlarge to life size; and having made friends with M. Bellagarda, the King’s treasurer, he was introduced with much difficulty, owing to the frequent visits of the Doge, into the royal apartments to retouch the portrait from life. Now whilst he stood painting, and the King with great courtesy admiring, there entered presumptuously into the apartments at smith of the Arsenal, presenting an ill-done portrait by himself, and saying that, while His Majesty was dining in the Arsenal, he had done the likeness of him. His presumption was humbled by a courtier who snatched it from his hand, and ripping it up with his dagger threw it into the neighbouring Grand Canal: which incident, on account of the whispering it produced, made it difficult for the painter to carry out his intention. Tintoretto had also observed on that occasion that from time to time certain persons were introduced to the King, whom he touched lightly on the shoulder with his rapier, adding other ceremonies. And pretending not to understand the meaning, he asked it of Bellagarda, who said that they were created knights by His Majesty, and that he, Tintoretto, might prepare himself to receive that degree; for he had discussed the matter with the King, to whom Tintoretto’s conditions were known and who had shown himself disposed, in attestation of his powers, to create him also a knight; but our painter, not being willing to subject himself to any title, modestly rejected the offer.” When the portrait was finished and presented to the King, it was acclaimed by him as a marvellous likeness, and we may safely conclude from this that it was fair to look on. The King presented it to the Doge. Perhaps the picture from the first had been intended as a present for Mocenigo, and this was the explanation of the secrecy observed in regard to it.

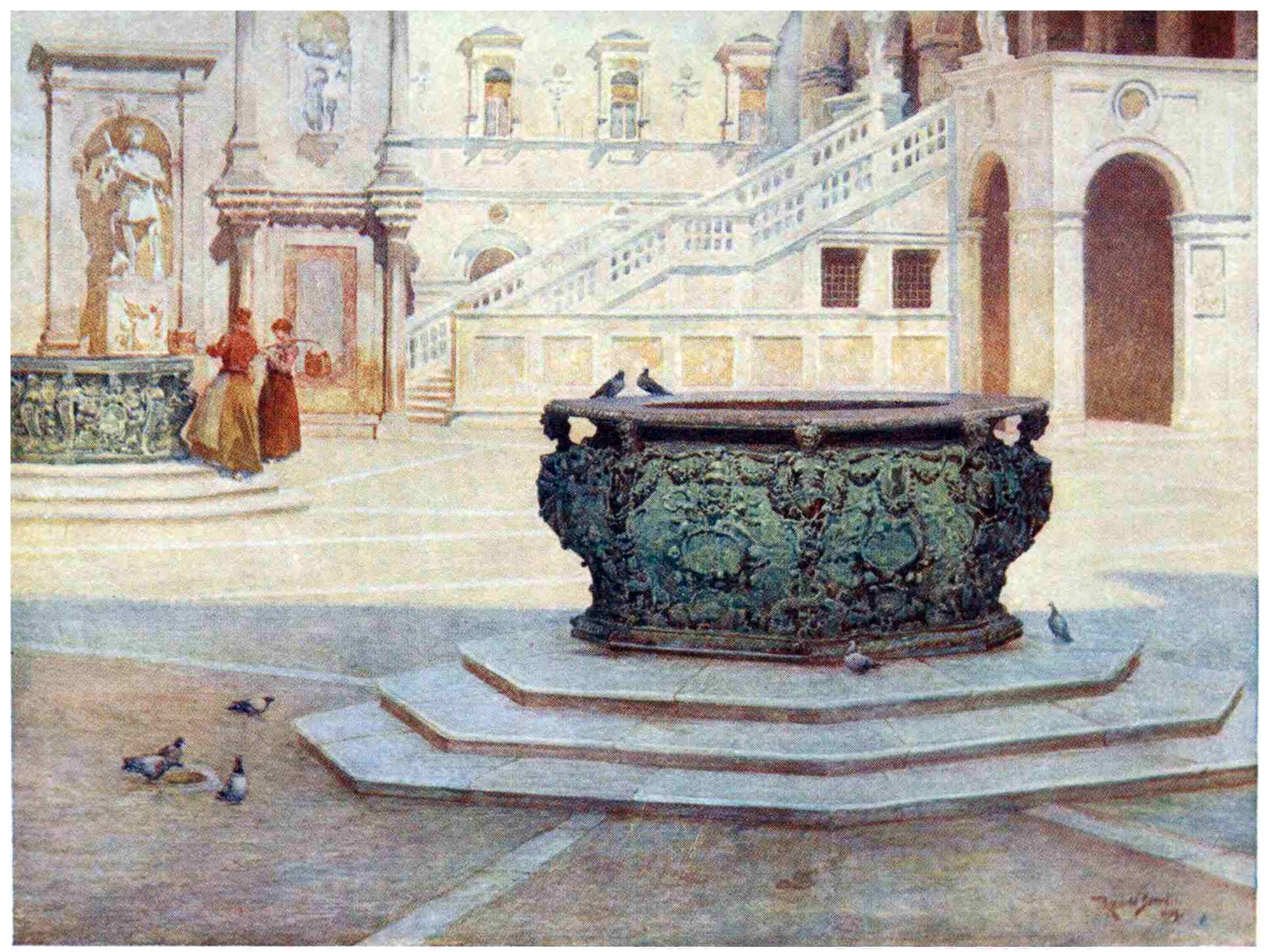

COURTYARD OF PALAZZO DUCALE.

The climax of entertainment was reached in the festa at the Ducal Palace on the second Sunday after Henry’s arrival (his visit lasted ten days). The glories of Venice were gathered in that marvellous hall still hung with the paintings of Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini, and the exquisite Paradise of Guariento; for it was yet a year previous to the great fire which was to give scope to the contemporary giants. The later victories of Venice were as yet unchronicled except in the hearts of living men. There was no thought of sumptuary laws on this day at least of the great festival. Ladies were there clothed all in ormesine, adorned with jewels and pearls of great size, not only in strings on their necks, but covering their head-dresses and the cloaks on their shoulders. “And in their whiteness, their beauty and magnificence, they formed a choir not so much of nymphs as of very goddesses. They were set one behind the other in fair order upon carpeted benches stretching round the whole hall, leaving an ample space in the centre, at the head of which was set a royal seat with a covering of gold and entirely covered with a baldaquin from top to bottom, and round it yellow and blue satin.” All the splendours of Venetian and Oriental cloths were lavished on the Hall of the Great Council and the Sala del Scrutinio adjoining. The King as usual entered whole-heartedly into the festivity. His seat was raised that he might look over the company, “but he chose nevertheless to go round and salute all the ladies with much grace and courtesy, raising his cap as he went along.” After a time musical instruments were heard, the ladies were carried off by the gentlemen, and forming into line they began to dance a slow measure, passing before the King and bowing as they passed. “And he stood the whole while cap in hand.” The French courtiers were permitted by their master to lay aside their mourning for the time, and they danced with great merriment, vying with the most famous dancers of Venice. But the great feature of the evening was the tragedy by Cornelio Frangipani—a mythological masque in honour of the most Christian King and of Venice herself—with Proteus, Iris, Mars, Amazons, Pallas and Mercury as protagonists. To the first printed edition of his masque Frangipani prefixed an apology for his title of tragedy, with the usual appeal to classic precedent. “This tragedy of mine,” he says, “was recited in such a way as most nearly to approach to the form of the ancients; all the players sang in sweetest harmony, now accompanied, now alone; and finally the chorus of Mercury was composed of players who had so many various instruments as were never heard before. The trumpets introduced the gods on to the appointed scene with the machinery of tragedy, but this could not be used to effect on account of the great concourse of people; and the ancients could not have been initiated into the musical compositions in which Claudio Merulo had reached a height certainly never attained by the ancients.” The masque is in reality a mere masque of occasion, comparable to countless English productions in the Elizabethan age, though lacking in the lyrical grace they generally possess. Henry is addressed as the slayer of monsters, the harbinger of peace, the herald of the age of gold—

Pregamo questo domator de’ mostri

Ch’eterno al mondo viva,

Perchè in pregiata oliva

Ha da cangiar d’ alloro

E apportar l’ antica età del’ oro.

The masque is without literary merit, but we need not regard it in the cold light of an after day, caged and with clipped wings. To that glorious assembly, illumined by the great deeds fresh in men’s minds and the presence of a royal hero, Frangipani’s words may well have been kindled into flame. For if time and place were ever in conspiracy to wing pedestrian thoughts and words, it must have been at this fêting of the most Christian King of France in the City of the Sea.

Pens were busy in Venice during the days of Henry’s stay. Unsalaried artists, independent of everything except a means of livelihood, exacted toll from the royal guest. From the 16,000 scudi of largess distributed by the King, payments are enumerated “to writers and poets who presented to His Majesty Latin works and poems made in praise of his greatness and splendour.” Gifts, as well as compliments were exchanged on all hands. The Duke of Savoy presented the Doge’s wife with a girdle studded with thirty gold rosettes each containing four pearls and a precious jewel in the centre, worth 1,800 scudi. And Henry’s final token of gratitude to his entertainers was to send after the Doge, who had accompanied him to Fusina, a magnificent diamond ring, begging that Mocenigo should wear it continually in token of their love. Most of these offerings and acknowledgments, without doubt, would be merely ceremonial. Yet the young King’s delight in his visit had been genuine, and his frank enjoyment of all Venice offered had won him her sympathy and even her affection. Memories of the freedom of his stay went with him to the routine of his kingship, and he looked backwards with delight to her winged pleasures. She had spread gifts out before him, as she does before all, but in his own hands he had carried the key of her inmost treasures; for his spirit was joyful and joy is the key to the unlocking of her heart.