Chapter Five

A MERCHANT OF VENICE

“SIAMO NOI calcolatori” was the confession of a modern Venetian, quoted lately as expressive of the spirit that governs Venice to-day and has lain at the root of her policy in the past. The confession is striking; for most men, however calculating in practice, acknowledge an ideal of spontaneous generosity which causes them to shun the admission of self-interested motives. The charge, if charge it can be termed, is an old one. Again and again it has been brought against Venice by those to whom her greatness has been a stumbling-block—“sono calcolatori.” But perhaps if the indictment be rightly understood it will be found to need, not so much a denial as an extension, a fuller statement of meaning. And this Professor Molmenti has supplied in his Venice in the Middle Ages.1 “The Venetians,” he says, in commenting on the support they lent to the Crusades, “never forgot their commercial and political interests in their zeal for the faith; they intended to secure for themselves a market in every corner of the globe. But their so-called egoism displayed itself in a profound attachment to their country and their race; and these greedy hucksters, these selfish adventurers, as they are sometimes unjustly called, had at bottom a genuine belief in objects high and serious; the merchant not seldom became a hero. These lords of the sea knew how to wed the passion of Christianity to commercial enterprise, and welded the aspirations of the faith with the interests of their country, proving by their action not only how vain and sterile is an idealism which consumes itself in morbid dreams, but also that the mere production of riches will lead to ruin unless it be tempered, legalised, almost, we would say, sanctified, by the serene and lifegiving breath of the ideal.” But because she was supremely successful in her undertakings, Venice won for herself much perplexed and hostile comment from those who were jealous of a mastery sustained with such apparently effortless self-possession—of an organisation so complete, so silent, so pervasive. She has been accused of perfidy, of cruelty, in short, of shameless egoism. A nation, a state, is pledged to the preservation of its identity, its conceptions must be bounded and constantly measured by the power of other states. The neighbours of Venice in the days of her glory were selfish and calculating also; her prominence was due not so much to special weapons as to her skill in wielding weapons everywhere in use.

And what can we say of the ends to which she directed her success, the scope of her arts, the nature of her pleasures? It must be admitted by all that the soul of Venice was capacious, unique in its harmony of imagination and political acumen; unique in its power of commanding and retaining respect. A great soul was in the men of Venice; it was present in all their activities, in their commerce as in their art. The two were most intimately allied. Again and again the chroniclers of Venice crown their catalogue of her glories with the reminder that their foundation is in commerce, that the Venetians are a nation of shopkeepers, and “you have only come to such estate by reason of the trade done by your shipping in various parts of the world.” Even in the fifteenth century it was deemed complimentary to say to a newly elected Doge, “You have been a great trader in your young days.” The greatness of Venice was coincident with the greatness of her trade. She was lit, it is true, with the ancient stars of her splendour after the mortal blow had been struck at her commerce by the discovery of the Cape route to the East, but the old unity of her strength had been lost—the firm foundations of the days when the nobles of Venice had been the directors of her enterprise. And at the end of the fifteenth century they no longer sat, in their togas, behind the counters in Rialto, or made the basements of their houses into stores. They had ceased to apprentice their sons to the merchants on the sea-going galleys. They still acted as commanders of the ships in times of war, but in intervals of peace the gulf between noble and merchant was constantly being enlarged. The commercial traveller was no longer considered one of the most distinguished of citizens. The corner stone had been taken from the building of Rialto; it had begun to crumble to the dissolution lamented by Grevembroch in his strange book on Venetian costumes. In the great days of Venice her commerce was great, and she knew how to robe it in glory, how to attract to it the noblest, and not the meanest, of her sons. Her shops were the objects of her proudest solicitude, and the well-being of her merchants the first of her cares. The hostels provided for foreign traders ranked with the most sumptuous of her palaces, and the rules framed for their guidance were amongst the most liberal in her legislature.

The calculations of Venice, growing with her growth, impressed on her national consciousness the importance of her position midway between the East and the West—her geographical qualification for becoming the mart of the world. With steady and concentrated purpose she devoted her energy to opening up fresh channels of communication. Sometimes by the marriage of a son or daughter of the Doge with the heir of a kingdom or a prince of Constantinople, sometimes by the subjugation of a common foe, Venice wove new threads of intercourse with the East. She always took payment for benefits she conferred in wider trading advantages. Her merchant vessels were not private adventures, they represented state enterprise and were under the control of the central government, travelling with the fleet and capable of reinforcing it at need. Seven merchant convoys left Venice annually for Roumania, Azof, Trebizond, Cyprus, Armenia, France, England, Flanders, Spain, Portugal and Egypt. By means of these vessels the glories of the Orient found their way to the lands of the West; Venice was mistress of the treasures of Arabia, and became their dispenser to Europe. And she was not merely a mart, a counter of interchange; she tested the goods at their source; she was not at the mercy of valuers, her citizen travellers came into touch with the goods on the soil that produced them. The East, to which the art of Venice owes much of its material—its gold, its gems, its colours—was not an unfathomed mine but, in a certain sense, a pleasure-ground for her citizens; they passed to and fro familiarly, guests of its greatest potentates. They stood face to face with Cublay Kaan, the monarch of mystery.

The journeys of the famous Poli are among the most thrilling and significant records of Venetian history. Through them we are able to realise something of the Republic’s debt to the lands of the East—a debt not to be summed up in enumeration of embroidery and jewels and perfumes and secrets of colour. In part at least it consisted of legends and traditions that filtered into Venice through the hearing and speech of her travellers—age-old lessons in wisdom, which must have invested some of the common things of Venetian life with new meaning and done something to break down the barriers which ignorance erects between man and man, knowledge and knowledge. In the beautiful Persian rendering of the story of The Three Magi, as told by Marco Polo, she came into touch with comparative theology, the familiar Christian tale drawn from an earlier source. Marco Polo tells how he first found at Sara the beautiful tombs of Jaspar, Melchior and Balthasar, with their bodies completely preserved; how the people of that place knew nothing of their history save that they were the bodies of kings; but three days’ journey onward he had come to the city of the fire-worshippers and been informed of the three who had set out to worship a newly born Prophet, carrying with them gifts to test the extent of his powers—gold for the earthly King, myrrh for the physician, incense for the God. “And when they were come there where the Child was born, the youngest of these three Kings went all alone to see the Child, and there he found that it was like himself, for it seemed of his age and form. Then he went out much marvelling, and after him went in the second of the Kings, who was near in age to the first, and the Child seemed to him, as to the first, of his own form and age, and he also went out much perplexed. Then went in the third, who was of great age, and it happened to him as to the other two, and he also went out very pensive. And when all the Kings were together, they told one another what they had seen; and they marvelled much and said they would go in all three together. Then they went together into the Child’s presence, and they found Him of the likeness and age that He really was, for He was only three days old. Then they adored Him and offered Him their gold and incense and myrrh. The Child took all their offerings and gave them a closed box, and then the three Kings departed and returned to their country.” Marco Polo goes on to relate how the Kings, finding the box heavy to bear, sat down by a well to open it, and, when they had opened it, they found only stones inside. These, in their disappointment, they threw into the well and lo! from the stones fire ascended which they gathered up and took home with them to worship. With it they burned all their sacrifices, renewing it from one altar to another. Other tales he told them from the wisdom of the East—of the idealist who found no joy in earthly existence, and the chagrin of his father the King, who surrounded him with luxury and with beautiful maidens, but could not persuade him. One day he rode out on his horse and saw a dead man by the way. And he was filled with horror at a sight which he had never seen before, and he asked those who were with him the meaning of the sight, and they told him it was a dead man. “What,” said the son of a King, “then do all men die?” Yes, truly, they say. Then the youth asked no more, but rode on in front in deep thought. And after he had ridden some way he met a very old man who could not walk, and who had no teeth, for he had lost them all by reason of his great age. And when the King’s son saw the old man he asked what he was and why he could not walk, and his companions told him that he could not walk from age, and that from age he had lost his teeth. And when the King’s son understood about the dead man and the old man, he returned to his palace, and said to himself that he would live no longer in so evil a world, but that he would go “in search of Him who never dies, of Him who made him. And so he departed from his father and from the palace, and went to the mountains, that are very high and impassable, and there he lived all his life, most purely and chastely, and made great abstinence, for certainly if he had been a Christian, he would be a great saint with our Lord Jesus Christ.” Did he find his answer in the mountains? Perhaps in some dawn or sunset he learned of the nature of “Him who made him, of Him who never dies”; perhaps among the wild creatures he learned before he was old to sing the lauds of our sister Death. But Polo’s comment on the story is interesting, for the Venetians would have little natural sympathy with its hero. They would prefer Carpaccio’s fairy prince who forsook his kingdom to follow Ursula and her virgins. The tale of one who dared not look on life in company with his kind, would strike a chill across the full-blooded natures of Venice, so eager to grasp at all that ministered to enjoyment and vitality.

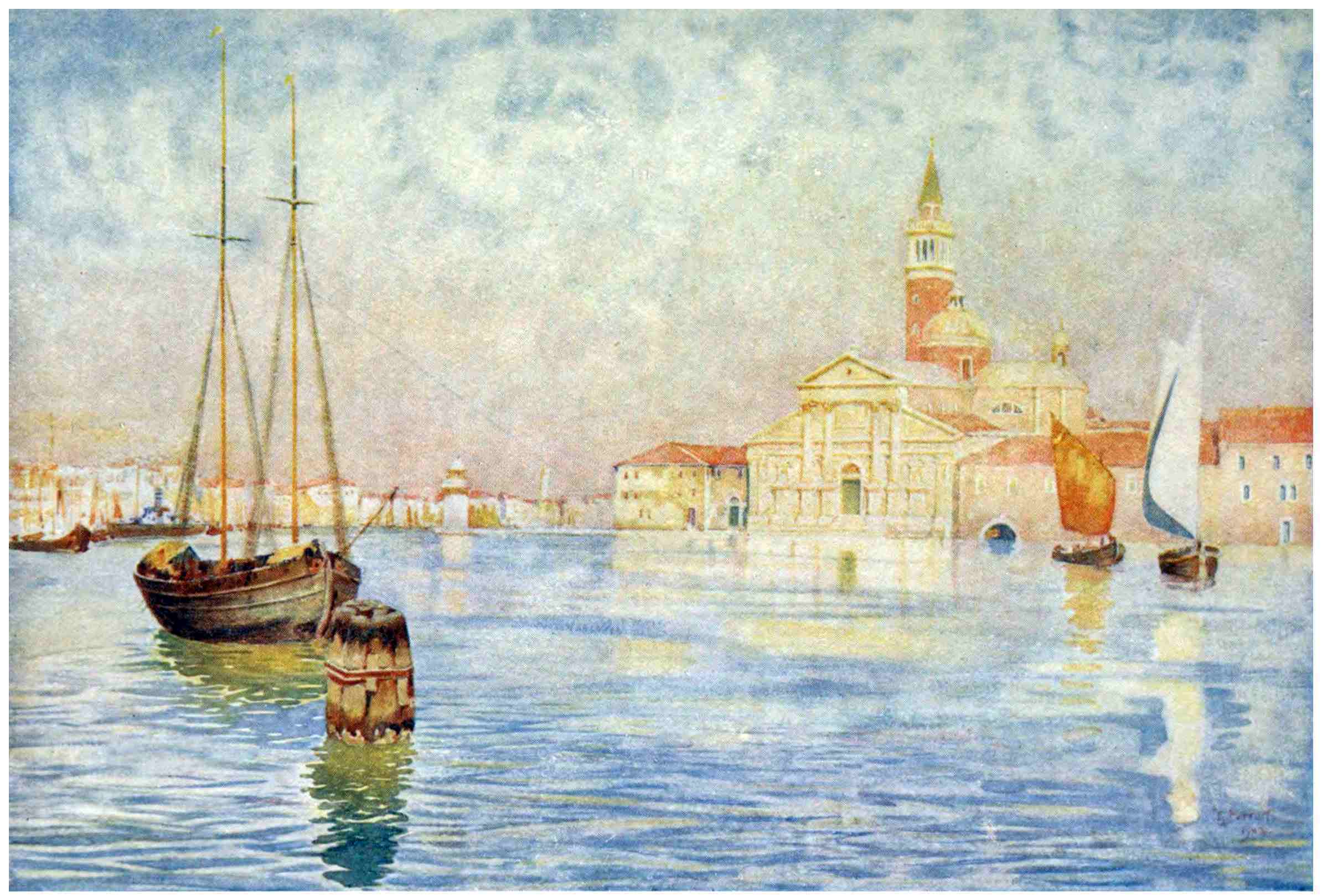

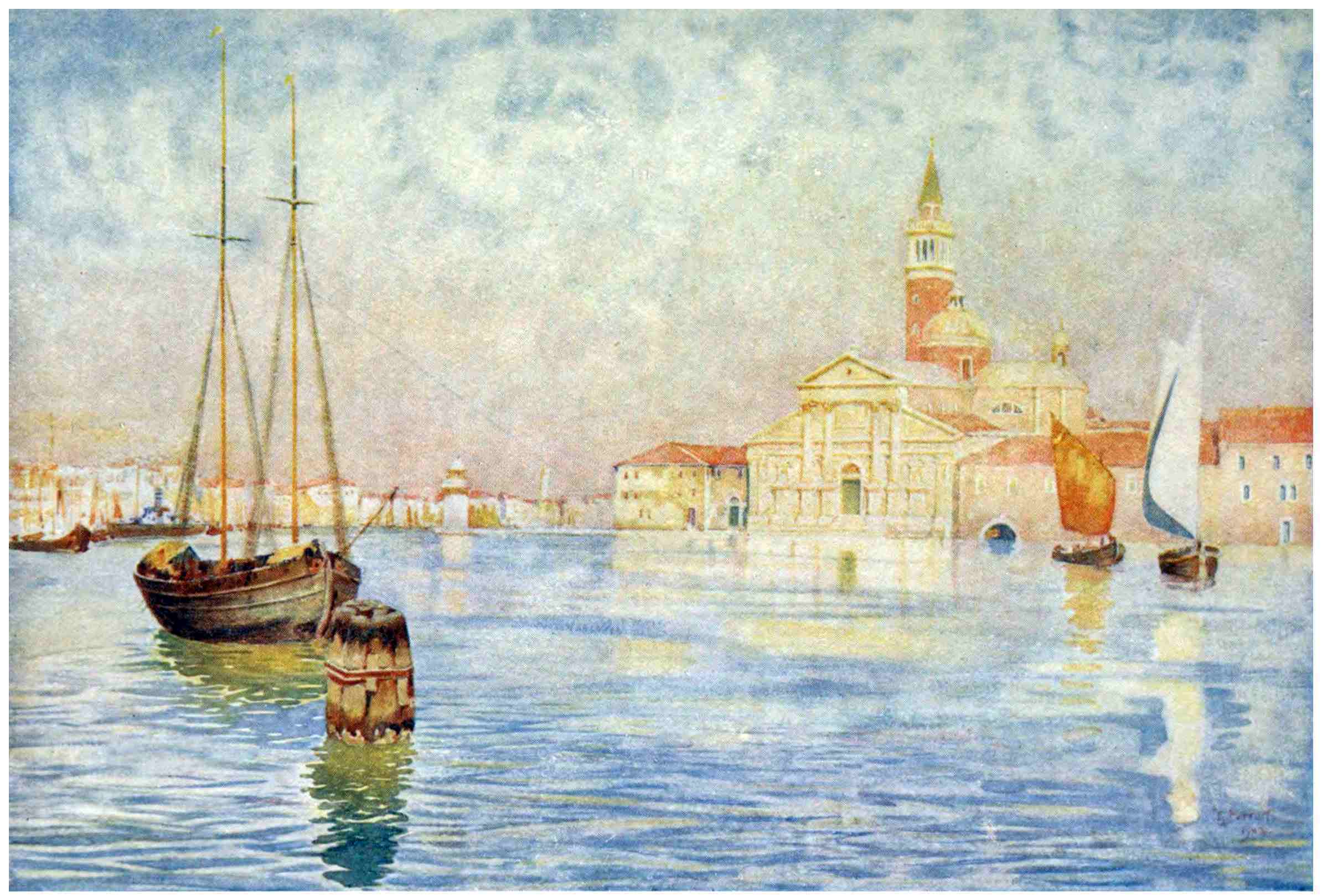

SAN GIORGIO.

But Marco’s pack held stories of a more tangible kind—tales of the Palace of Cublay Kaan, with its hall that held six thousand men, the inside walls covered with gold and silver and pictures of great beasts, and the outside rainbow-coloured, shining like crystal in the sun, and a landmark far and wide. And within the circuit of the palace walls was a green pleasure mound covered with trees from all parts and with a green palace on its summit. “And I tell you that the mound and the trees and the palace are so fair to see that all who see them have joy and gladness, and therefore has the great Sire had them made, to have that beautiful view and to receive from it joy and solace.” He tells of the wonderful Zecca where coins of the Great Kaan are stamped—not made of metal, but of black paper—which may be refused nowhere throughout the Kaan’s dominions on pain of death. All who are possessed of gold and treasure are obliged to bring goods several times in the year, and receive coins of bark in exchange; and therefore, Marco explains, “is Cublay richer than all else in the world.” He describes the posting system, the rich palaces built for the housing of messengers, the trees planted along the merchant routes to act as signposts on the road; “for,” he says, “you will find these trees along the desert way, and they are a great comfort to merchant and messenger.” Visitors to the chapel of San Giorgio dei Schiavoni will recall the use that Carpaccio has made of these palm-tree signposts in the Death of St. Jerome and the Victory of St. George. Marco tells of magnificent feasts made by the Great Kaan on his birthday and on New Year’s Day. He delights in stories of the chase within the domain of Cublay’s palace of Chandu (perhaps the Xanadu of Coleridge) the walls of which enclosed a sixteen-mile circuit, with fountains and rivers and lawns and beasts of every kind. He describes in detail, as of special interest to his hearers, the size and construction of the rods of which the Palace of Canes was built and the two hundred silken cords with which it was secured during the summer months of its existence. He speaks of the “weather magic” by which rain and fog are warded off from this palace; and of the Great Kaan’s fancy that the blood of a royal line should not be spilt upon the ground to be seen of sun and air, and of his consequent device for the murder of his uncle Nayan, whom he tossed to death in a carpet. Baudas (Baghdad), he says, is the chief city of the Saracens. A great river flows through it to the Indian Ocean, which may be reached in eighteen days. The city is full of merchants and of traffic; it produces nasich and nac and cramoisy, and gold and silver brocades richly embroidered with design of birds and of beasts; and the woods of Bastra, between Baudas and the sea, produce the finest dates in the world. He recounts the taking of this Baudas in the year 1255 by Alaü, the Great Kaan’s brother, who, when he had taken it, discovered therein a tower belonging to the Caliph full of gold and silver and other treasure, so that there never was so much seen at one time in one place. When Alaü beheld the great heap of treasure, he was amazed and sent for the Caliph into his presence and asked him why he had amassed so great a treasure and what he had intended to do with it. “Did you not know that I was your enemy and coming to lay you waste?” he demanded. “Why, therefore, did you not take your treasure and give it to knights and soldiers to defend you and your city?” The caliph replied nothing, for he did not know what to answer. So Alaü continued, “Caliph, I see you love your treasure so much, I will give you this treasure of yours to eat.” So he had the Caliph shut up in the tower and commanded that nothing should be given him to eat or drink, saying, “Caliph, eat now as much treasure as you will, for you shall never eat or drink anything else.” And he left the Caliph in the tower, where, at the end of four days, he died. Marco must have opened up to his listeners in Venice horizons of lands almost comparable in extent to the sea-spaces familiar to their thoughts from infancy. He spoke of deserts of many days’ journey, of the port of Hormos at the edge of one of the most beautiful of the plains—a city whence precious stones and spices and cloths of silver and gold brought by the merchants from India were shipped to all parts of the world.

But the Poli brought more tangible trophies than the most circumstantial of tales in their pack. Foolish artists might have held themselves rich with these, but the honour of their family would demand better credentials before welcoming fantastically arrayed strangers into its bosom. The courtyard of the house behind the Malibran, at which on their return from their travels they demanded admission, is known still as the Corte del Milione, and its walls are still enriched with Byzantine cornice and moulding, and with sculptured beasts as strange as any to be met with in Cublay’s preserves. The three travellers had the appearance of Tartars, and from long disuse of their language they spoke in broken Italian. Tradition tells of the way in which they heaped exploit upon exploit in the attempt to convince their incredulous relatives of their identity; and at last, according to Ramusio, they invited a number of their relations to a superb banquet, at which they themselves appeared in long robes of crimson satin. When the guests were set down, these robes were torn into strips and distributed amongst the servants. Through various metamorphoses of damask and velvet they came at last to the common dresses in which they had arrived. And when the tables were moved and the servants had gone, Marco, as being the youngest, began to rip up the seams and welts of these costumes and take out from them handfuls of rubies and sapphires, carbuncles, diamonds and emeralds. There was no longer any doubt or delay; the shaggy tartar beards had lost all their terrors. These men, who had suddenly displayed “infinite riches in a little room,” must undoubtedly be what they claimed to be; happy the family to which the magicians belonged; the Doge’s Palace need not be afraid to welcome them; they must be set high in the State.

Yet the accumulation of treasure was by no means the most noteworthy act of their drama. The Poli had been more than mere traders; from the first they had been diplomatists of a high order. Their career seems to give us the key to some of the wonderful faces that appear in the crowds pictured by Venetian painters, especially those of Carpaccio. They are the faces of men who have met the crisis of life unalarmed, by virtue of a combination of daring and wisdom which is no common possession. They are not cold; if they are severe they are full of feeling—sensitive to the pathos and humour as well as the sternness of reality. The Poli had been obliged to furnish themselves with patience in lands where the transit of a plain is measured in weeks; three years’ residence in a city of Persia is mentioned as a matter of detail. We are not told the reason of delay, only that they could not go before or behind. They had travelled in the true spirit of adventure. On that first journey, when Marco was not of the company, the Great Kaan’s messengers, who came to request an interview for their master, who had never set eyes on a Latin, had found the two brothers open-minded and trustful. They had acquitted themselves well in Cublay’s presence, answering all his questions wisely and in order. He had inquired as to the manners and customs of Europe, and particularly as to Western methods of government and the Christian Church and its Head. He had been “glad beyond measure” at what he had heard of the deeds of the Latins, and decided to send a request to the Christian Apostle for one hundred men learned in the Christian law and the Seven Arts and capable of teaching his people that their household gods were works of the devil and why the faith of the West was better than theirs. The thought of the lamp burning before the sepulchre of God in Jerusalem had stirred his imagination, and he craved some of its oil for the light of his temple, or, maybe, his pleasure dome. So the two Venetians had set out for Europe on his strange embassy. They were provided with a golden tablet on which the Kaan had inscribed orders for the supplying of their needs, food, horses, escorts in all the countries through which they should pass. At the end of three years, after long delays on account of the snows, they arrived at the port of Layas in Armenia, and from Layas they had come to Acre in April of the year 1269. At Acre they had found that Pope Clement IV was dead, and no new election had as yet been made. Venetian history teems with dramatic situations, but it would be difficult to find any stranger than that in which the Polo brothers now found themselves placed. Merchants of Venice, they came as ambassadors from the Lord of All the Tartars to demand missionaries from the Father of Christendom, who was not able to supply them because he was not in existence. In their dilemma at Acre they consulted Theobald of Piacenza, Legate of Egypt, who advised them to await the new Pope’s election and meanwhile to return to their homes. His advice was accepted, and the two brothers made their way onwards to Venice, where one of them, Nicolas, discovered his son, young Marco, a lad of fifteen years old. They remained in Venice for two years, but when, at the end of that time, no Pope had yet been elected, the brothers felt their return to the Kaan could be deferred no longer. There is something touching in their fidelity to the pledge they had given and the constancy of their merchant faith. They prepared to set out again. This time little Marco went with them on an absence that lasted for seventeen years, and was to gather a greater treasure for the world than any diamonds and rubies and velvets to be prodigally scattered on the floor of the Corte del Milione. At Acre they obtained Theobald’s permission to fetch some of the holy oil desired by the Kaan from Jerusalem. The journey to Jerusalem performed, they returned once more to Acre, and finally set forth on their return journey to the Kaan with a letter from Theobald testifying that they had done all in their power, “but since there was no Apostle, they could not carry the embassy.” But when they had gone as far on their journey as Layas, they were followed by letters from Theobald, who was now Pope Gregory of Piacenza, begging their return. They complied with great joy and set sail for Acre in a galley provided for their use by the King of Armenia. This was the hour of their triumph, for they were received by the Pope with great honour, given costly presents for the Kaan, and provided with two friars of very great learning. The names of these two are possibly better withheld, for they were more learned than courageous. When they had come as far on their journey as Layas, their incipient fears of the land of the Tartars were wrought to a pitch by the sight of the Saracen Army which was being brought against Armenia by the Sultan of Babylon, and they insisted on handing their credentials over to the Poli and returning at once to Italy. And the brothers were forced to go on their way with worse than no preachers of their faith, with tidings of their defection.

For three and a half years they journeyed on, detained often by floods and bad weather. The news of their coming travelled before them to the Kaan, and he sent his servants forty days’ journey to meet them. The Kaan received them with joy, was graciously pleased with the letters and credentials sent by the Pope, and accepted young Marco as his liegeman and responsible messenger. Marco sped well in learning the language, customs and writing of the Tartars, but it is clear he must have acquired other than scholastic accomplishments. He was endowed with tact and power of observation, and returned from his first embassy full of news of the men and customs he had encountered; “for he had seen on several occasions that when the messengers the Great Kaan had sent into various parts of the world returned and told him the results of the embassy on which they had gone, and could tell him no other news of the countries where they had been, the Kaan said they were ignorant fools.” For seventeen years young Messer Marco was employed in continual coming and going. He was learned in many strange and hidden things, and was placed in honour high above the barons—the darling of Cublay’s heart. Again and again the three Venetians asked for leave of absence to visit their country, but so great was the love Cublay bore to them that he could not bear to be parted from them; until at last an embassy arrived from Argon, King of Levant, asking for a new wife of the lineage of his dead wife Bolgana, and the Kaan is persuaded by Argon’s messengers to allow Marco and his two uncles to depart with them in charge of the lady. They set out by sea, and after some twenty months’ sailing and many disasters arrived at their destination. King Argon was dead, and the lady Cocachin was bestowed on his son. Of the six hundred followers who had set out with them on their journey only eighteen had survived it. Their mission accomplished, the Poli made their way to Trebizond, from Trebizond to Constantinople and from Constantinople to Venice. This was in the year 1295.

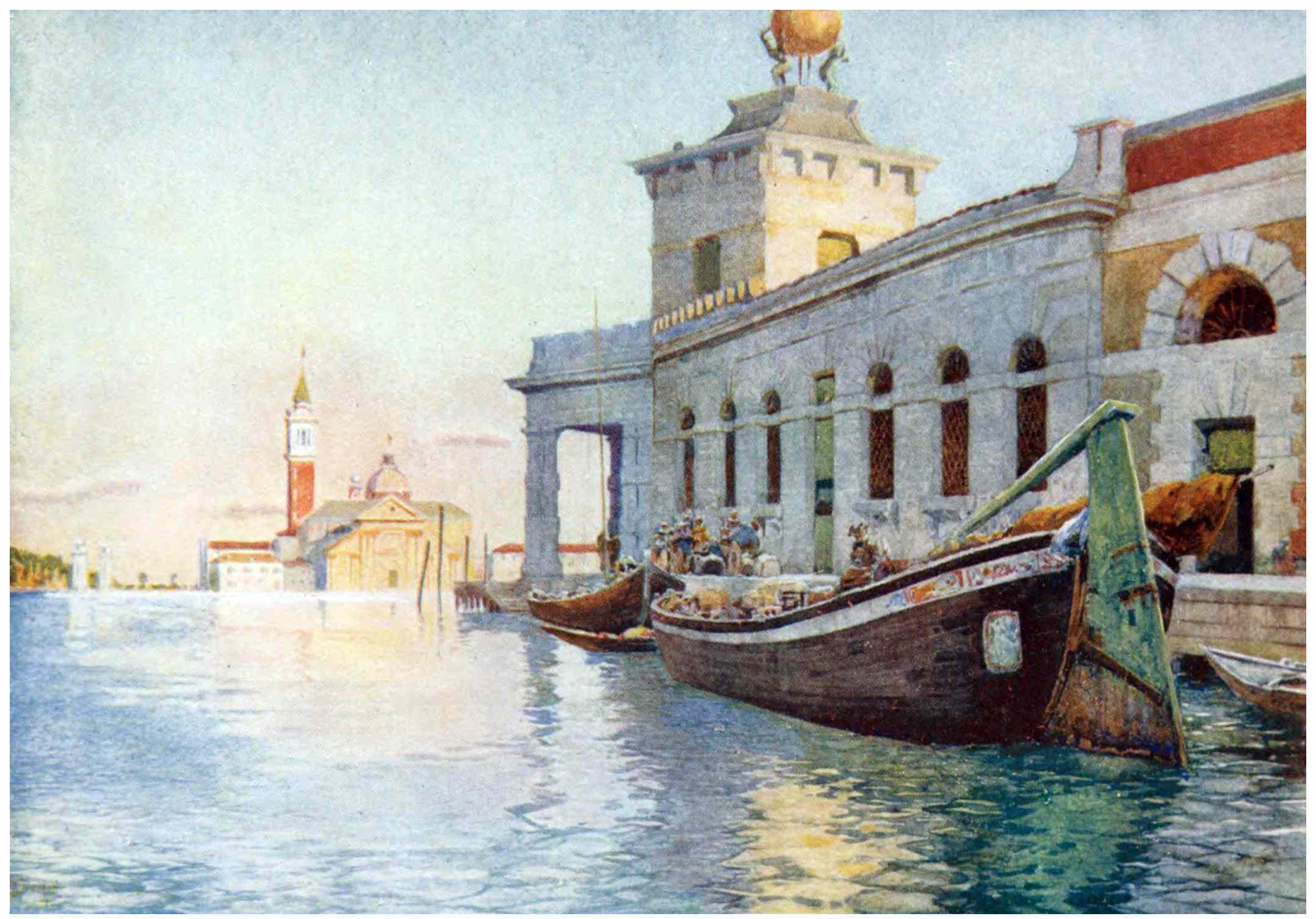

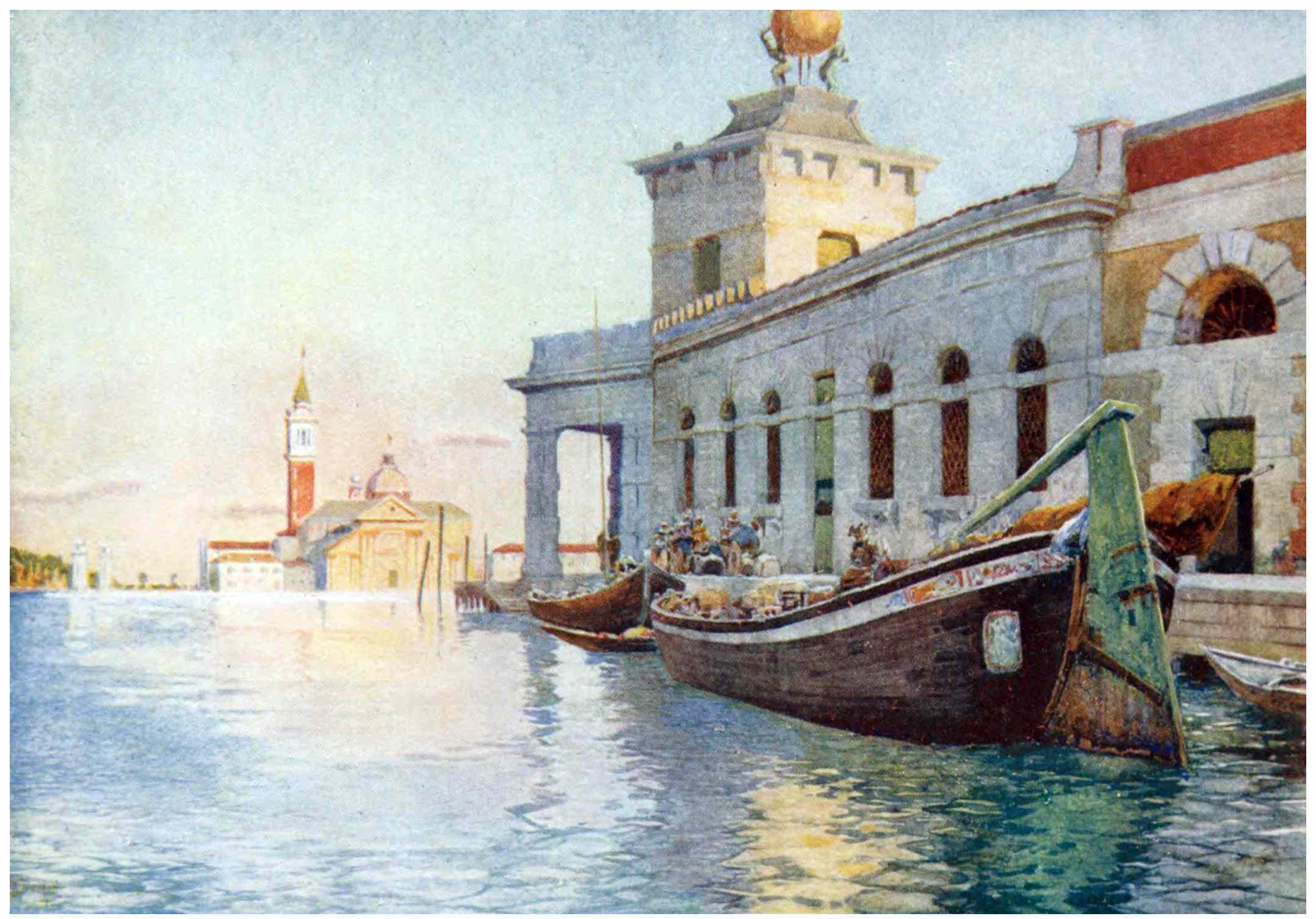

THE DOGANA.

And how would Venice, the place of his birth, reveal herself to Marco, now he had seen so many wonders and glories in distant lands? We may imagine the sun to have been setting as the travellers turned into the Lido port, dropping a globe of molten fire vast and mysterious through the haze, while the last dim rays gleamed golden on the windows of the Riva degli Schiavoni. Venice lay among her waters, blue and glittering, interspersed with jewelled marsh. The last gulls of those that so gallantly had dipped and sailed all day upon the water were flying home, their breasts and wings radiant in the level sunlight round the home-coming ship. Many citizens of Venice must have been at the Lido port, thronging to meet the merchant vessels, to greet their friends or to have news of them from others. But none came to meet these three travellers; alone they embarked in a gondola bearing their cargo with them. Venice had clothed herself in all her beauty to give them welcome. Which of Cublay’s glories could rival this splendour of the lagoon with its countless treasures of light? The marsh lay in unequal patches, each outlined with a luminous silver rim—a magic carpet of dusky olive, threaded with strands of radiant azure and sprinkled with ruby and amethyst. As their gondola moved slowly down towards the city, the boats of the night fishers passed with the silence of shadows between them and the glow. And when here and there a fisher alighted on the marsh or moved across it like a spirit stepping on the waters, he must have seemed to Marco the very memory and renewal of those strange Eastern stories of which his mind was full. So, under the mystic glow of the desert, he had seen figures of the caravan rise and move against the tinted haze of the oasis. Onwards glided the boat towards the Basin of San Marco—westward the luminous wonder of lagoon and marsh, and a cold, clear intensity of stirring water to the east. And as they drew nearer and ever nearer, our travellers’ hearts beat high with the wonders of the city of their birth. The stars were piercing the night sky in countless numbers: the yellow lights of the city quivered along the Riva: the masts of the fishing-fleet swung clear against the pale western glow in the waterway of the Giudecca: the flowing tide wound silver coils about the black shadows of their hulls. Past the Dogana, keystone of Venice to the Eastern traveller, their little boat moved down the quiet waters of the Grand Canal, deep into the heart of that great shadowy city, apparent Queen over all the glories of the Cities of the East.

1 Translated by Mr. Horatio Browne.